Functor–Applicative–Monad 위계의 한계를 넘어, Category/Arrow를 토대로 효과를 서술·분석하는 방법을 살피고, 병렬 합성, 분기(ArrowChoice), 효과 트리 분석과 mermaid 도식화, 그리고 Arrow 표기법까지 간단한 예제와 함께 다룹니다.

지난 글에서는 작은 프로그램 안에서 효과를 시퀀싱하는 여러 방법을 살펴봤습니다. 아직 읽지 않았다면 그 글부터 시작하길 권하지만, 굳이 아니라도 따라오지 못할 정도는 아닙니다.

Applicative, Monad, 그리고 Selective Applicative를 검토했고, 각 시스템은 저마다의 트레이드오프가 있었습니다. 우리는 모든 접근이 “표현력”과 “분석 가능성” 사이의 스펙트럼 어딘가에 놓여 있음을 확인했고, 글의 끝에서는 더 나은 무언가를 원하게 되었죠. 표현력에서는 Monad가 최강입니다. 우리가 쓰고 싶은 어떤 프로그램이든 표현할 수 있으니까요. 하지만 그 대가로, 프로그램을 실행하지 않고서는 그 프로그램을 분석할 수 있는 능력을 사실상 제공하지 않습니다.

반면 Applicative와 Selective Applicative는 합리적인 수준의 프로그램 분석을 제공하지만, 복잡한 프로그램을 표현할 수는 없습니다. 상류의 효과 결과에 실질적으로 의존하는 하류의 효과를 인코딩하는 것조차 불가능하죠.

이들 접근은 모두 동일한 Functor–Applicative–Monad 위계에 기반합니다. 이번 글에서는 그 축을 잠시 내려놓고 전혀 다른 토대 위에서 다시 쌓아, 더 나은 결과를 낼 수 있는지 확인해 보겠습니다.

본격적으로 시작하기 전에, Monad 위계에서 부족하다고 느꼈던 점과 새로운 시스템에서 얻고 싶은 것을 비판적으로 생각해 봅시다.

내 희망 목록은 다음과 같습니다:

이 요구 사항을 보면, Monadic 효과 시스템의 가장 큰 문제는 이전 효과의 결과를 다루는 방식이 지나치게 거칠다는 점입니다. 이를 bind의 시그니처를 다시 보면 알 수 있습니다:

(>>=) :: Monad m => m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

이전 효과의 결과가 임의의 Haskell 함수로 전달되고, 그 함수의 역할은 프로그램의 전체적인 이어짐(continuation)을 반환하는 것입니다! 이는 그 함수가 어떤 실행에서든 프로그램의 나머지 전체를 바꿔치기할 수 있게 허용합니다. 저는 이것이 대부분의 합리적인 프로그램이 요구하는 수준을 훨씬 넘어서는 권한이라고 봅니다. 솔직히 말해, 이 정도의 표현력은 위험합니다. 정적 분석만으로도 어떤 경로들이 “가능할지”조차 식별할 수 없는 프로그램을 대체 어떻게 작성하고 계신가요? 분기, 루프, 재귀처럼 더 복잡한 흐름조차 이 정도의 대형 망치(sledgehammer) 같은 동적성에 의존하지 않고도 더 구조화된 방식으로 표현할 수 있습니다.

이는 우리가 프로그램을 어느 정도 제약할 여지가 있음을 말해 줍니다. 그리고 그 제약을 알뜰하게 사용한다면, 그 권한을 우리가 바라는 이점과 맞바꿀 수 있습니다.

과거의 결과를 여전히 활용해야 하지만, 판도라의 상자를 열지는 말아야 합니다. 즉, 실행 시점에 임의의 Haskell 함수를 돌려 “새로운 효과”를 만들어내지 못하도록 주의해야 합니다. 그러니 Monad처럼 continuation을 만드는 함수를 쓰지 않고 결과를 사용하려면, 효과의 입력과 출력을 효과 시스템의 “구조” 안에 의미 있게 포함시켜야 합니다. 또한 이 효과들을 체인으로 연결할 수 있어야 하니, 합성 수단도 필요합니다.

이미 감이 왔다면, 이는 Category 타입클래스에 아주 잘 들어맞습니다:

class Category k where

id :: k a a

(.) :: k b c -> k a b -> k a c

이것만으로도 우리가 원하는 것의 상당 부분을 제공합니다. 출력이 함수 클로저를 통해 프로그램의 continuation에 구워져 있는 Monad와 달리, Category 구조는 입력과 출력을 구조의 일부로서 명시적으로 라우팅합니다. 놀랍지 않게도 아주 자연스러운 적합입니다. 결국 “Category 이론”이지 “Monad 이론”은 아니잖아요…

이제 이전 글의 예제들을 이 새로운 Category 기반 효과 시스템으로 다시 구현해 보기 시작합시다. 시간을 아끼기 위해, 위계를 조금 건너뛰어 한 번에 Arrow까지 올라가 보겠습니다.

Arrow 클래스가 낯설다면, 모양은 대략 이렇습니다:

class Category a => Arrow (a :: Type -> Type -> Type) where

arr :: (b -> c) -> a b c

(***) :: a b c -> a b' c' -> a (b, b') (c, c')

다른 메서드도 몇 가지 따라오지만, 이것이 우리가 정의해야 할 최소 셋입니다.

Category가 상위 클래스이므로, 그쪽의 동일성과 합성을 그대로 씁니다. arr를 통해 순수 Haskell 함수를 Category 구조 안으로 들어 올릴 수 있습니다. 방금 임의의 Haskell 함수를 피하고 싶다고 했지만, 여기서는 Applicative처럼 그 함수가 순수하므로, 함수 내부의 효과나 효과의 구조를 알아낼 수 없습니다. 문제없습니다.

(***)는 잠시 후에 다시 보겠습니다.

그럼 시작해 봅시다. 지난 글에서 Applicative로 작성했던 프로그램을 다시 구현해 볼까요?

귀찮을 테니, 그때 했던 일을 여기 다시 요약해 둡니다:

import Control.Applicative (liftA3)

import Control.Monad.Writer (Writer, runWriter, tell)

class (Applicative m) => ReadWrite m where

readLine :: m String

writeLine :: String -> m ()

data Command

= ReadLine

| WriteLine String

deriving (Show)

-- | We can implement an instance which runs a dummy interpreter that simply records the commands

-- the program wants to run, without actually executing anything for real.

instance ReadWrite (Writer [Command]) where

readLine = tell [ReadLine] *> pure "Simulated User Input"

writeLine msg = tell [WriteLine msg]

-- | A helper to run our program and get the list of commands it would execute

recordCommands :: Writer [Command] String -> [Command]

recordCommands w = snd (runWriter w)

-- | A simple program that greets the user.

myProgram :: (ReadWrite m) => String -> m String

myProgram greeting =

liftA3

(\_ name _ -> name)

(writeLine (greeting <> ", what is your name?"))

readLine

(writeLine "Welcome!")

-- We can now run our program in the Writer applicative to see what it would do!

main :: IO ()

main = do

let commands = recordCommands (myProgram "Hello")

print commands

-- [WriteLine "Hello, what is your name?", ReadLine, WriteLine "Welcome!"]

이 Applicative 버전의 핵심은, Applicative 제약만 필요로 하는 어떤 프로그램이든 그 프로그램이 수행할 순차적 효과의 전체 목록을 분석해 낼 수 있었다는 점입니다.

이제 같은 프로그램을 Arrow 제약으로 효과를 인코딩해서 작성해 보겠습니다.

먼저 단서를 하나: Arrow 기반으로 프로그램을 쓰면 보기 흉합니다. 하지만 걱정 마세요, 잠깐만 버텨 주세요. 나중에 이 문제를 다루겠습니다.

Applicative 버전과 마찬가지로, 이번에도 ReadWrite 효과 집합에 대한 인터페이스를 타입클래스로 정의하되, 이번에는 Arrow 제약을 가정합니다:

import Control.Arrow

import Control.Category

import Prelude hiding (id)

class (Arrow k) => ReadWrite k where

-- Readline has no interesting input, so we use () as input type.

readLine :: k () String

-- We track the inputs for the writeLine directly in the Category structure.

writeLine :: k String ()

-- Helper for embedding a static Haskell value directly into an Arrow

constA :: (Arrow k) => b -> k a b

constA b = arr (\_ -> b)

-- | A simple program which uses a statically provided message to greet the user.

myProgram :: (ReadWrite k) => String -> k () ()

myProgram greeting =

constA (greeting <> ", what is your name?")

>>> writeLine

>>> readLine

>>> constA "Welcome!"

>>> writeLine

좋습니다. 꽤 직관적으로 느껴질 겁니다. 이런 순차적 Applicative 프로그램을 변환하는 것은 사소합니다.

실행하려면 여전히 IO monad를 써야 합니다. base에서 IO가 그렇게 되어 있으니까요. 하지만 멋진 Kleisli 뉴타입 래퍼를 쓰면 임의의 모나딕 연산을 Arrow로 감싸 Arrow로 만들 수 있습니다. 모나딕 효과를 Arrow 구조에 삽입하는 셈입니다.

Kleisli IO의 ReadWrite 인스턴스는 다음과 같습니다:

instance ReadWrite (Kleisli IO) where

readLine = Kleisli $ \() -> getLine

writeLine = Kleisli $ \msg -> putStrLn msg

run :: Kleisli IO i o -> i -> IO o

run prog i = do

runKleisli prog i

잘 돌아갑니다:

>>> run (myProgram "Hello") ()

Hello, what is your name?

Chris

Welcome!

Kleisli를 좀 더 자세히 봅시다:

newtype Kleisli m a b = Kleisli { runKleisli :: a -> m b }

익숙하죠? 모나딕 bind의 continuation 함수가 숨어 있습니다.

하지만 차이가 있습니다. 이제 그 임의의 함수가 우리의 “인터페이스”가 아니라 “구현”의 일부가 되었다는 점이요!

이게 중요한 이유는, ReadWrite 인터페이스의 다른 구현을 만들어서, 임의의 bind와 씨름하지 않고도 효과만 추적할 수 있기 때문입니다.

그렇게 해 봅시다. 명령을 기록하는 구현을 만들어 보죠.

data Command

= ReadLine

| WriteLine

deriving (Show)

-- Just like the applicative we create a custom implementation of the interface which for static analysis.

-- The parameters are phantom, we won't be running anything, so we only care about

-- the structure of the effects for now.

data CommandRecorder i o = CommandRecorder [Command]

-- We need a Category instance since it's a pre-requisite for Arrow:

instance Category CommandRecorder where

-- The identity command does nothing, so it records no commands.

id = CommandRecorder []

-- Composition of two CommandRecorders just collects their command lists.

(CommandRecorder cmds2) . (CommandRecorder cmds1) = CommandRecorder (cmds1 <> cmds2)

-- Now the Arrow instance.

instance Arrow CommandRecorder where

-- We know this function must be pure (barring errors), so we don't

-- need to track any effects from it.

arr _ = CommandRecorder []

-- Don't worry about this combinator yet, we'll come back to it.

-- For now we'll collect the effects from both sides.

(CommandRecorder cmds1) *** (CommandRecorder cmds2) = CommandRecorder (cmds1 <> cmds2)

-- | Now implementing the ReadWrite instance is just a matter of collecting the commands

-- the program is running.

instance ReadWrite CommandRecorder where

readLine = CommandRecorder [ReadLine]

writeLine = CommandRecorder [WriteLine]

-- | A helper to run our program and get the list of commands it would execute

recordCommands :: CommandRecorder i o -> [Command]

recordCommands (CommandRecorder cmds) = cmds

-- | Here's a helper for printing out the effects a program will run.

analyze :: CommandRecorder i o -> IO ()

analyze prog = do

let commands = recordCommands prog

print commands

프로그램을 분석해 보면, 실행했을 때 어떤 효과가 수행될지 보여 줍니다:

>>> analyze (myProgram "Hello")

[WriteLine,ReadLine,WriteLine]

좋아요. Applicative 버전과 동등한 수준으로 프로그램을 분석하고 실행할 수 있게 되었네요. 하지만 사용자에게 이름을 물어보고는 그냥 무시해 버리는 건 우스꽝스럽지 않나요? 사실 Arrow 인터페이스는 정량적으로 더 표현력이 큽니다. 과거 효과의 결과를 다음 효과에서 활용할 수 있으니까요! 이제 writeLine이 동적으로 입력을 받을 수 있게 허용했으므로, 더 이상 명령 자체의 구조에 출력을 기록하지 않습니다. 이게 한 발 후퇴처럼 느껴질 수 있지만, 예전 방식을 원한다면 물론 이렇게 정의할 수도 있습니다: writeLineStatic :: String -> k () (). Arrow는 어떤 쪽을 택할지 선택할 유연성을 제공합니다. 이 부분은 글의 뒷부분에서 조금 더 이야기하겠습니다.

Applicative로는 할 수 없던 일을 해 봅시다. 사용자가 제공한 이름으로 인사하도록 프로그램을 바꿔 보죠. 그러는 김에 인사말도 입력으로 받으면 어떨까요?

-- | This program uses the name provided by the user in the response.

myProgram2 :: (ReadWrite k) => k String ()

myProgram2 =

arr (\greeting -> greeting <> ", what is your name?")

>>> writeLine

>>> readLine

>>> arr (\name -> "Welcome, " <> name <> "!")

>>> writeLine

Arrow 합성으로 한 효과의 결과를 다음 효과로 라우팅할 수 있고, arr는 Functor의 fmap처럼 값을 변환할 수 있게 해 줍니다. 효과의 구조는 여전히 “정적으로” 정의되어 있으므로, 입력을 라우팅하더라도 전체 프로그램을 미리 분석할 수 있습니다:

>>> analyze myProgram2

[WriteLine, ReadLine, WriteLine]

>>> run myProgram2 "Hello"

Hello, what is your name?

Chris

Welcome, Chris!

멋지죠!

좋은 출발입니다. 과거 효과의 결과를 활용할 수 있는 능력은 이미 Selective Applicative보다 개선되었고, Applicative 버전에서 가졌던 분석 능력도 희생하지 않았습니다.

하지만 현재까지의 프로그램은 모두 선형적인 명령 시퀀스일 뿐입니다. 앞선 효과의 결과를 프로그램 훨씬 뒤쪽에 있는 효과로 라우팅하려면 어떻게 할까요?

조금 더 강한 도구가 필요합니다. 아까 무시했던 (***)를 다시 꺼내 오고, 이와 함께 (&&&)도 보겠습니다. (***)를 구현하면 (&&&)는 공짜로 따라옵니다.

(***) :: Arrow k => k a b -> k c d -> k (a, c) (b, d)

(&&&) :: Arrow k => k a b -> k a c -> k a (b, c)

이 연산자들은 Arrow 인터페이스 안의 두 개의 독립적인 프로그램을 서로 “병렬”로 합성하게 해 줍니다. 여기서 “병렬”의 의미는 (Arrow 법칙 범위 내에서) 구현체에 달려 있지만, 핵심은 양쪽이 서로 의존하지 않는다는 점입니다. 우리가 지금까지 (>>>)로 하던 순차 합성과는 다릅니다.

이제 값들을 이리저리 라우팅하고, 앞선 효과의 값을 뒤쪽으로 전달할 수 있는 조금 더 복잡한 프로그램을 써 봅시다.

import UnliftIO.Directory qualified as Directory

-- The effects we'll need for this example

class (Arrow k) => FileCopy k where

readLine :: k () String

writeLine :: k String ()

copyFile :: k (String, String) ()

data Command

= ReadLine

| WriteLine

| CopyFile

deriving (Show)

-- Here's the real executable implementation

instance FileCopy (Kleisli IO) where

readLine = Kleisli $ \() -> getLine

writeLine = Kleisli $ \msg -> putStrLn msg

copyFile = Kleisli $ \(src, dest) -> Directory.copyFile src dest

-- Helper prompting the user for input.

prompt :: (FileCopy cat) => String -> cat a String

prompt msg =

pureC msg

>>> writeLine

>>> readLine

fileCopyProgram :: (FileCopy k) => k () ()

fileCopyProgram =

( prompt "Select a file to copy"

&&& prompt "Select the destination"

)

>>> copyFile

이 프로그램은 사용자의 소스 파일과 목적지 파일을 각각 묻고, 소스를 목적지로 복사합니다. 특히 각 프롬프트는 서로 독립적입니다. 즉, 서로에 대한 “데이터 의존성”이 없습니다. 하지만 copyFile은 두 개의 인자를 받습니다. 두 프롬프트의 결과죠. (&&&)가 이를 표현하게 해 줍니다.

실행해 봅시다:

>>> run fileCopyProgram ()

Select a file to copy

ShoppingList.md

Select the destination

ShoppingList.backup

음, 결과가 눈에 보이지는 않지만, 진짜로 동작합니다! Kleisli의 (***) 구현은 왼쪽을 먼저 실행하고 그 다음에 오른쪽을 실행합니다. 하지만 다른 용도에서 실제 병렬 실행이 필요하다면, 각 쌍을 Concurrently 같은 것으로 병렬 실행하는 구현을 작성해도 됩니다. 그러면 데이터 의존성이 허락하는 만큼 프로그램이 “마법처럼” 병렬로 변할 겁니다! 물론 주의는 필요하지만, 적어도 그런 선택지가 있다는 건 좋습니다. 데이터 의존성이 숨겨져 있는 Monadic 인터페이스에서는 이런 걸 기대하기 어렵죠.

이제 분석해 봅시다.

물론 실행될 효과들의 “목록”을 수집해 출력할 수도 있겠지만, 솔직히 그건 좀 지루합니다. 이제 순차 합성과 병렬 합성이 모두 가능해졌으니, 프로그램은 “연산 트리”가 됩니다. 분석 도구 역시 그에 맞춰야겠지요.

효과 전체 트리를 추적하는 방식으로 CommandRecorder를 다시 작성해 봅시다:

-- | We can represent the effects in our computations as a tree now.

data CommandTree eff

= Effect eff

| Identity

| Composed (CommandTree eff {- >>> -}) (CommandTree eff)

| -- (***)

Parallel

(CommandTree eff) -- First

(CommandTree eff) -- Second

deriving (Show, Eq, Ord, Functor, Traversable, Foldable)

data CommandRecorder eff i o = CommandRecorder (CommandTree eff)

instance Category (CommandRecorder eff) where

-- The identity command does nothing, so it records no commands.

id = CommandRecorder Identity

-- I collapse redundant 'Identity's for clarity.

-- The category laws make this safe to do.

(CommandRecorder Identity) . (CommandRecorder cmds1) = CommandRecorder cmds1

(CommandRecorder cmds2) . (CommandRecorder Identity) = CommandRecorder cmds2

(CommandRecorder cmds2) . (CommandRecorder cmds1) = CommandRecorder (Composed cmds1 cmds2)

instance Arrow (CommandRecorder eff) where

-- We don't bother tracking pure functions, so arr is a no-op.

arr _f = CommandRecorder Identity

-- Track when we fork into parallel execution paths as part of the tree.

(CommandRecorder cmdsL) *** (CommandRecorder cmdsR) = CommandRecorder (Parallel cmdsL cmdsR)

-- | The interface implementation just tracks the commands

instance FileCopy (CommandRecorder Command) where

readLine = CommandRecorder (Effect ReadLine)

writeLine = CommandRecorder (Effect WriteLine)

copyFile = CommandRecorder (Effect CopyFile)

analyze :: CommandRecorder Command i o -> IO ()

analyze prog = do

let commands = recordCommands prog

putStrLn $ renderCommandTree commands

이제 효과 트리를 만들 수 있으니, 이걸 그대로 트리로 렌더링해 봅시다!

다음 함수는 mermaid 다이어그램 언어로 흐름도를 기술하는 문자열로 프로그램 트리를 렌더링합니다.

제 mermaid 렌더러 구현은 평가하지 말아 주세요… 더 멋진 버전이 있다면 꼭 보내 주세요 :)

(그리 중요하진 않으니, 건너뛰어도 괜찮습니다)

diagram :: CommandRecorder Command i o -> IO ()

diagram prog = do

let commands = recordCommands prog

putStrLn $ commandTreeToMermaid commands

-- | A helper to render our command tree as a flow-chart style mermaid diagram.

commandTreeToMermaid :: forall eff. (Show eff) => CommandTree eff -> String

commandTreeToMermaid cmdTree =

let preamble = "flowchart TD\n"

(outputNodes, links) =

renderNode cmdTree

& flip runReaderT (["Input"] :: [String])

& flip evalState (0 :: Int)

in preamble

<> unlines

( links

<> ((\output -> output <> " --> Output") <$> outputNodes)

)

where

newNodeId :: (MonadState Int m) => m Int

newNodeId = do

n <- get

put (n + 1)

return n

renderNode :: CommandTree eff -> ReaderT [String] (State Int) ([String], [String])

renderNode = \case

Effect cmd -> do

prev <- ask

nodeId <- newNodeId

let cmdLabel = show cmd

nodeDef = show nodeId <> "[" <> cmdLabel <> "]"

links = do

x <- prev

pure $ x <> (" --> " <> nodeDef)

pure ([nodeDef], links)

Identity -> do

nodeId <- newNodeId

prev <- ask

let nodeDef = show nodeId <> ("[Identity]")

let links = do

x <- prev

pure $ x <> (" --> " <> nodeDef)

pure ([nodeDef], links)

Composed cmds1 cmds2 -> do

(leftIds, leftNode) <- renderNode cmds1

(rightIds, rightNode) <- local (const leftIds) $ renderNode cmds2

pure (rightIds, leftNode <> rightNode)

Parallel cmds1 cmds2 -> do

prev <- ask

nodeId <- newNodeId

let nodeDef = show nodeId <> ("[Parallel]")

(leftIds, leftNode) <- local (const [nodeDef]) $ renderNode cmds1

(rightIds, rightNode) <- local (const [nodeDef]) $ renderNode cmds2

let thisLink = do

x <- prev

pure $ x <> (" --> " <> nodeDef)

links =

thisLink

<> leftNode

<> rightNode

pure (leftIds <> rightIds, links)

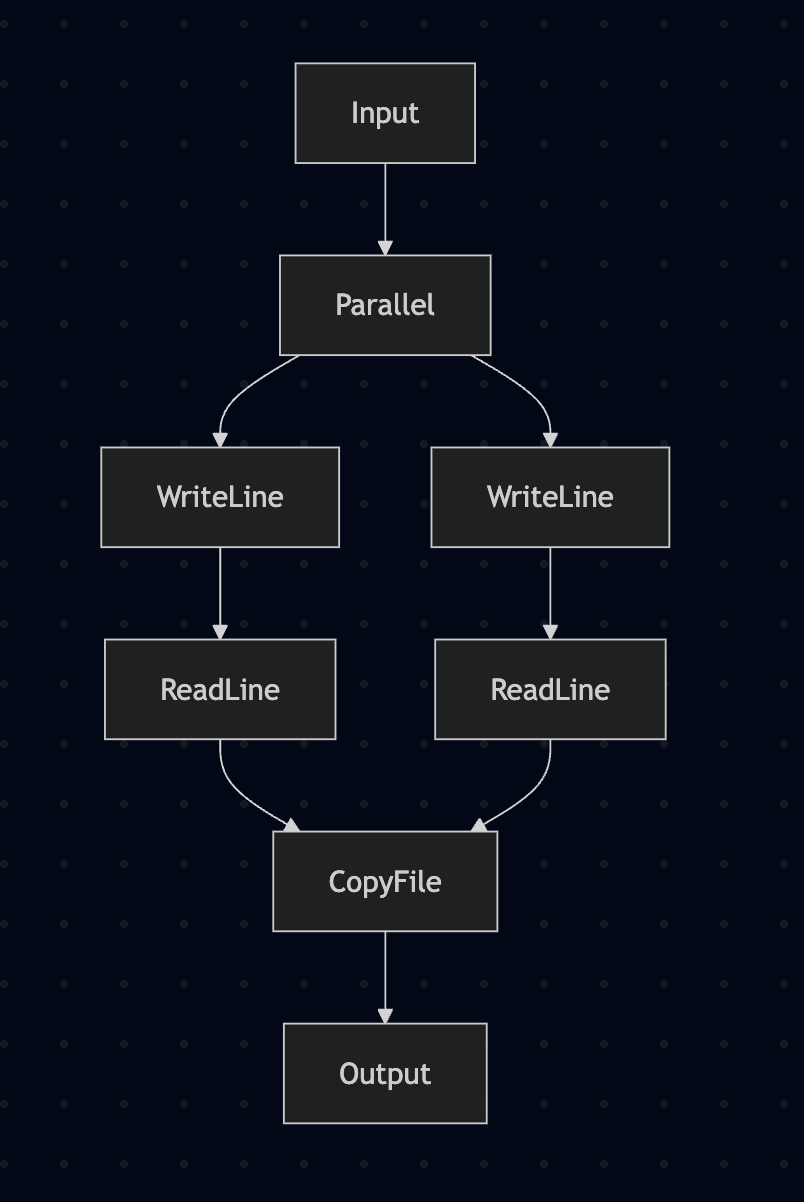

fileCopyProgram의 다이어그램 출력은 다음과 같습니다:

>>> diagram fileCopyProgram

flowchart TD

Input --> 0[Parallel]

0[Parallel] --> 1[WriteLine]

1[WriteLine] --> 2[ReadLine]

0[Parallel] --> 3[WriteLine]

3[WriteLine] --> 4[ReadLine]

2[ReadLine] --> 5[CopyFile]

4[ReadLine] --> 5[CopyFile]

5[CopyFile] --> Output

렌더링하면 이렇게 보입니다:

꽤 멋지지 않나요?

다이어그램화는 CommandTree로 할 수 있는 일 중 하나일 뿐입니다. 그냥 데이터이므로, 폴드해서 모든 효과를 얻을 수도 있고, 어떤 효과가 어떤 것에 의존하는지 분석할 수도 있고, 별별 일을 다 할 수 있습니다. 이는 Selective의 Over/Under 뉴타입이 주던 것보다 훨씬 명확한 그림을 줍니다.

아주 단순한 예제였지만, 약속합니다. arr, (***), first/second를 조합하면 원하는 어떤 식으로든 값을 라우팅할 수 있습니다.

하지만 아직 할 수 없는 것이 있습니다. 가능한 실행 경로들 사이에서 “분기”한 다음 그중 하나만 실행하는 것입니다.

그걸 이제 추가해 봅시다.

다행히 분기를 추가하는 일은 꽤 간단합니다. base에는 이름 그대로의 ArrowChoice가 있으니 구현해 보죠.

ArrowChoice는 새로운 조합자를 추가합니다:

(+++) :: ArrowChoice k => k a b -> k c d -> k (Either a c) (Either b d)

(***)가 서로 독립적인 두 프로그램을 “둘 다” 수행하는 단일 Arrow로 녹여내는 것과 유사하게, (+++)는 프로그램에 조건 분기를 도입해, 입력 값이 Left인지 Right인지에 따라 “오직 한 경로만” 실행되도록 해 줍니다.

(+++)를 구현하면, 비슷한 (|||)도 공짜로 얻습니다:

(|||) :: ArrowChoice k => k a c -> k b c -> k (Either a b) c

CommandTree에 Branch 케이스를 추가하고 CommandRecorder에 대해 ArrowChoice를 구현해 봅시다.

data CommandTree eff

= Effect eff

| Identity

| Composed (CommandTree eff {- >>> -}) (CommandTree eff)

| Parallel

(CommandTree eff) -- First

(CommandTree eff) -- Second

| Branch

(CommandTree eff) -- Left

(CommandTree eff) -- Right

deriving (Show, Eq, Ord, Functor, Traversable, Foldable)

instance ArrowChoice (CommandRecorder eff) where

(CommandRecorder cmds1) +++ (CommandRecorder cmds2) = CommandRecorder (Branch cmds1 cmds2)

문제없죠. 상기 차원에서, 지난번 Selective Applicative로 표현했던 분기 프로그램을 다시 보여 드립니다:

-- | A program using Selective effects

myProgram :: (ReadWriteDelete m) => m String

myProgram =

let msgKind =

Selective.matchS

-- The list of values our program has explicit branches for.

-- These are the values which will be used to crawl codepaths when

-- analysing your program using `Over`.

(Selective.cases ["friendly", "mean"])

-- The action we run to get the input

readLine

-- What to do with each input

( \case

"friendly" -> writeLine ("Hello! what is your name?") *> readLine

"mean" ->

let msg = unlines [ "Hey doofus, what do you want?"

, "Too late. I deleted your hard-drive."

, "How do you feel about that?"

]

in writeLine msg *> deleteMyHardDrive *> readLine

-- This can't actually happen.

_ -> error "impossible"

)

prompt = writeLine "Select your mood: friendly or mean"

fallback =

(writeLine "That was unexpected. You're an odd one aren't you?")

<&> \() actualInput -> "Got unknown input: " <> actualInput

in prompt

*> Selective.branch

msgKind

fallback

(pure id)

이 예제는 Selective Applicative의 한계 때문에 좀 억지스러웠습니다. 그래도 Arrow 설정으로 그대로 옮겨 보겠습니다.

먼저 CommandRecorder에 대해 ArrowChoice를 구현합시다.

-- Define our effects

class (Arrow k) => ReadWriteDelete k where

readLine :: k () String

writeLine :: k String ()

deleteMyHardDrive :: k () ()

-- New commands for the new effects

data Command

= ReadLine

| WriteLine

| DeleteMyHardDrive

deriving (Show)

-- Track the effects

instance ReadWriteDelete CommandRecorder where

readLine = CommandRecorder (Pure ReadLine)

writeLine = CommandRecorder (Pure WriteLine)

deleteMyHardDrive = CommandRecorder (Pure DeleteMyHardDrive)

-- Here's the runnable implementation

instance ReadWriteDelete (Kleisli IO) where

readLine = Kleisli $ \() -> getLine

writeLine = Kleisli $ \msg -> putStrLn msg

deleteMyHardDrive = Kleisli $ \() -> putStrLn "Deleting hard drive... Just kidding!"

그리고 ArrowChoice를 사용하는 프로그램은 다음과 같습니다:

branchingProgram :: (ReadWriteDelete k, ArrowChoice k) => k () ()

branchingProgram =

pureC "Select your mood: friendly or mean"

>>> writeLine

>>> readLine

>>> mapC

( \case

"mean" -> Left ()

"friendly" -> Right ()

-- Just default to friendly

_ -> Right ()

)

>>> let friendly =

pureC "Hello! what is your name?"

>>> writeLine

>>> readLine

>>> mapC (\name -> "Lovely to meet you, " <> name <> "!")

>>> writeLine

mean =

pureC

( unlines

[ "Hey doofus, what do you want?",

"Too late. I deleted your hard-drive.",

"How do you feel about that?"

]

)

>>> writeLine

>>> deleteMyHardDrive

in mean ||| friendly

다시 한 번 보듯, 이 버전은 Selective Applicative 버전보다 실제로 더 표현력이 큽니다. 사용자 이름으로 진짜로 인사해 주니까요. 친절하네요.

mermaid 렌더러의 수정은 생략하겠습니다. Branch는 Parallel과 거의 비슷합니다.

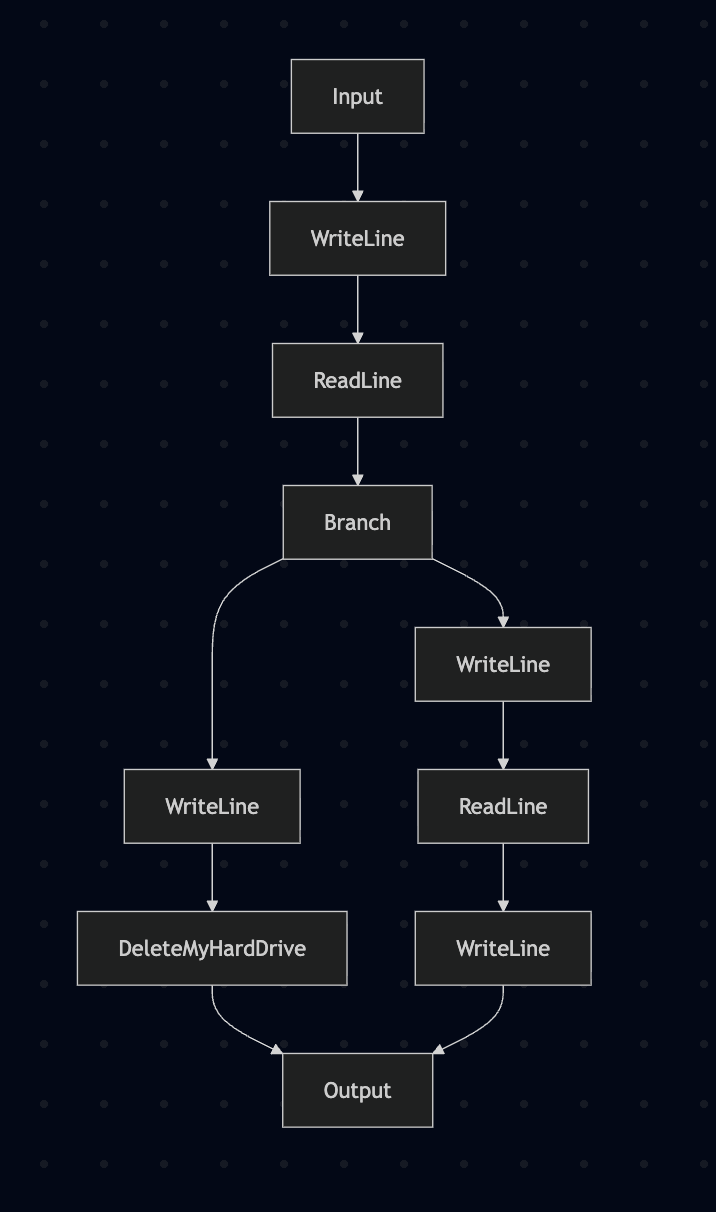

이전처럼 다이어그램을 만들어 봅시다:

>>> diagram branchingProgram

flowchart TD

Input --> 0[WriteLine]

0[WriteLine] --> 1[ReadLine]

1[ReadLine] --> 2[Branch]

2[Branch] --> 3[WriteLine]

3[WriteLine] --> 4[DeleteMyHardDrive]

2[Branch] --> 5[WriteLine]

5[WriteLine] --> 6[ReadLine]

6[ReadLine] --> 7[WriteLine]

4[DeleteMyHardDrive] --> Output

7[WriteLine] --> Output

분기마다 효과가 다르다는 게 이제 명확하죠?

물론 예상대로 실행도 됩니다:

>>> run branchingProgram

Select your mood: friendly or mean

friendly

Hello! what is your name?

Joe

Lovely to meet you, Joe!

>>> run branchingProgram

Select your mood: friendly or mean

mean

Hey doofus, what do you want?

Too late. I deleted your hard-drive.

How do you feel about that?

Deleting hard drive... Just kidding!

좋습니다. 방금 예제의 문법이 슬슬 험악해지기 시작했네요. Arrow용 do-notation 같은 게 있다면 얼마나 좋을까요…

{-# LANGUAGE Arrows #-} 프라그마를 켜면, Arrow에 대해 일종의 do-notation을 쓸 수 있습니다. 입력을 필요한 곳으로 자동으로 라우팅해 주고, if와 case도 ArrowChoice 조합자로 번역해 줍니다. 꽤 인상적이죠.

여기서 Arrow 표기법을 깊게 설명하지는 않겠습니다. 자세한 내용은 GHC 매뉴얼을 참고하세요.

분기 프로그램을 Arrow 표기법으로 옮기면 이렇게 됩니다:

branchingProgramArrowNotation :: (ReadWriteDelete k, ArrowChoice k) => k () ()

branchingProgramArrowNotation = proc () -> do

writeLine -< "Select your mood: friendly or mean"

mood <- readLine -< ()

case mood of

"mean" -> mean -< ()

"friendly" -> friendly -< ()

_ -> friendly -< ()

where

friendly = proc () -> do

writeLine -< "Hello! what is your name?"

name <- readLine -< ()

writeLine -< "Lovely to meet you, " <> name <> "!"

mean = proc () -> do

writeLine

-<

unlines

[ "Hey doofus, what do you want?",

"Too late. I deleted your hard-drive.",

"How do you feel about that?"

]

deleteMyHardDrive -< ()

익숙해지는 데 약간 시간이 걸리지만, 그리 나쁘지 않습니다.

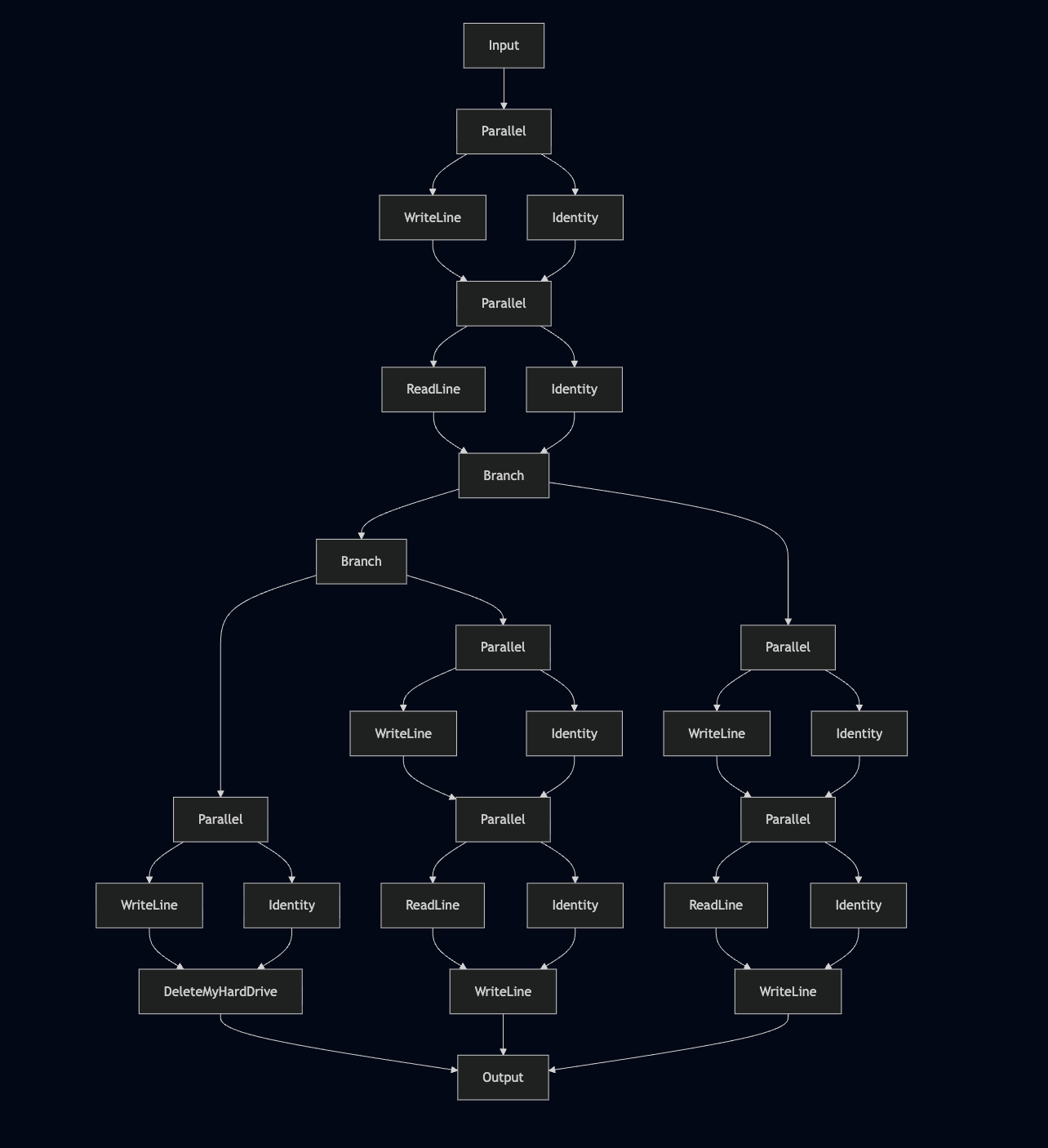

번역이 어떻게 되었는지 감을 잡기 위해 다이어그램을 봅시다:

그리 예쁘지는 않습니다. 번역 과정에서 반대편에 Identity를 넣으며 불필요한 Parallel 호출이 많이 생깁니다. Category 법칙상 Identity는 동작에 영향을 주지 않으니 완전히 유효하지만, 우리 관점에서는 지저분하고 다이어그램을 막히게 하니 정리해 봅시다.

중간 단계로 구축한 커맨드 트리는 그냥 값입니다. 그러니 마음대로 변환해 깔끔하게 만들면 됩니다.

Command와 CommandTree에 Data와 Plated를 파생시킨 뒤, 트리에 transform을 한 번 돌리면 됩니다. transform은 트리를 바닥부터 다시 만들면서 불필요한 Identity 노드를 제거합니다.

unredundify :: (Data eff) => CommandTree eff -> CommandTree eff

unredundify = transform \case

Parallel Identity right -> right

Parallel left Identity -> left

Composed Identity right -> right

Composed left Identity -> left

other -> other

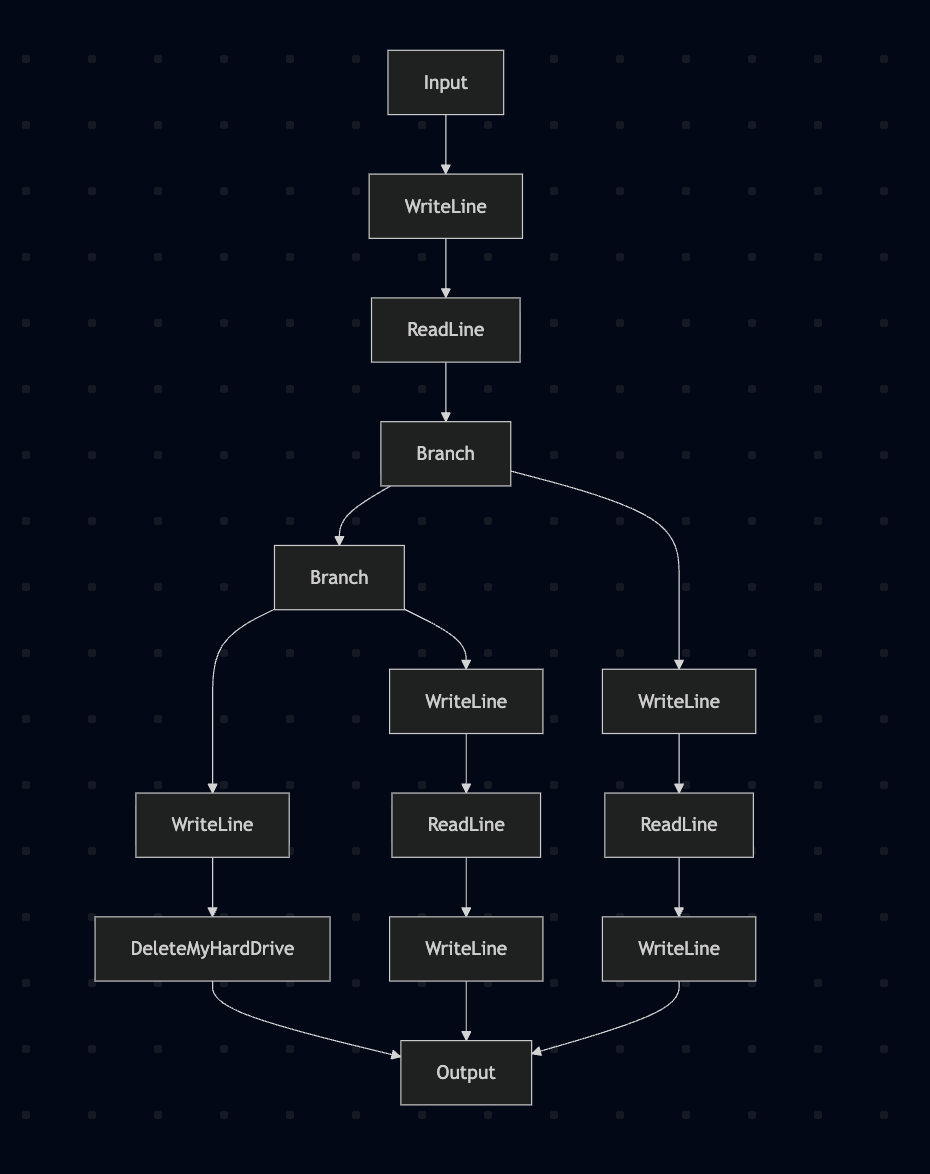

unredundify한 버전을 다이어그램으로 그리면 한결 깔끔합니다:

여기서 여러 팔(branch)을 이진 분기들의 시퀀스로 붕괴시키는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. 물론 완전히 올바른 동작입니다. 하지만 하나의 분기처럼 도식화하고 싶다면 Branch 생성자를 리스트를 받도록 바꾸고 다시 쓰기 규칙으로 모두 모아도 됩니다. Parallel도 마찬가지죠. 용도에 가장 유용한 방향으로 무엇이든 할 수 있습니다.

Arrow 표기법에는 몇 가지 특이점이 있지만, 인자 라우팅을 전부 수작업으로 하는 것에 비하면 상당한 개선입니다.

Arrow에서 정적 데이터와 동적 데이터의 차이에 대해 간단히 짚고 넘어가겠습니다. Applicative에서는 어떤 효과의 동작을 정의하는 데 필요한 모든 데이터가 “정적”이어야 합니다. 즉, 프로그램을 구성하는 시점에 알아야 하죠(물론 Haskell 전체 프로그램 레벨에서는 여전히 런타임일 수 있습니다).

Arrow에서는 정적 데이터와 동적 데이터를 섞을 수 있습니다. 이는 인터페이스 작성자에게 달려 있습니다.

예를 들어, 빌드 시스템을 구성한다면 인터페이스를 이렇게 만들 수 있습니다:

class (Arrow k) => Builder k where

dynamicReadFile :: k FilePath String

staticReadFile :: FilePath -> k () String

dynamicReadFile은 FilePath를 동적 입력으로 받습니다. 즉, 어떤 파일을 읽을지는 실행 시점이 되어야 압니다. 반면 staticReadFile은 FilePath를 정적 입력으로 받습니다. 프로그램을 구성할 때 Haskell 값으로 단일 FilePath를 전달합니다. 이 경우, 그 FilePath를 효과의 구조에 그대로 박아 둘 수 있으므로, 분석 단계에서도 접근할 수 있습니다.

이건 좀 더 고급 사례지만 매우 유용할 수 있습니다. 빌드 시스템의 경우, 정적으로 알려진 의존 파일들은 staticReadFile로 제공해 둘 수 있고, 빌드 시스템은 지난 실행 이후 해당 파일들이 바뀌었는지 확인한 다음, 그 서브트리의 의존성들에 변화가 없다면 안전하게 캐시된 결과로 일부 서브트리를 대체할 수 있습니다.

이런 류의 설계는 신중함을 요구하지만, 엄청난 유연성을 제공하고 완전히 새로운 프로그래밍 기법을 열어 줍니다.

Haxl을 들어보셨을 겁니다. Haskell에서 프로그램을 분석해 원격 데이터 소스에 대한 요청을 배치/캐시하는 라이브러리죠. Haxl의 구현과 인터페이스는 다소 복잡하고, Monad를 사용한다는 사실 때문에 할 수 있는 일에 제약이 있습니다. Arrow 기반 버전이 얼마나 효과적일지 궁금합니다.

여기서는 기본 프로그램을 작성하는 데 충분한 클래스들을 탐색했습니다. 이제 분기할 수 있고, 계산들 사이의 독립성을 표현할 수 있으며, 입력을 필요한 어디로든 라우팅할 수 있습니다. 여전히 좀 더 많은 표현력이 필요하다면, 몇 가지 클래스를 번개 투어로 훑어보죠.

ArrowLoop는 고정점(fixed point) 스타일의 재귀를 인코딩합니다.

class Arrow a => ArrowLoop a where

loop :: a (b, d) (c, d) -> a b c

흥미롭게도, 이는 사실 profunctors 패키지의 Costrong와 같은 이름 바꾸기라고 볼 수 있습니다.

정말정말 실행 중에 프로그램을 완전히 재구성해야 한다면, 실행 시점에 만들어진 Arrow를 적용하는 ArrowApply 클래스를 사용할 수 있습니다.

class Arrow a => ArrowApply a where

app :: a (a b c, b) c

이는 런타임에 전혀 새로운 코드 경로를 정의하는 미친 듯한 표현력을 줍니다. 실제로 “그게 꼭 필요”한 합리적인 프로그램은 드물다고 생각하지만, 때로는 지루함을 피하는 지름길이 되기도 합니다. 다만 app을 사용하면 동적으로 적용된 Arrow 내부의 효과는 분석에서 숨겨지게 됩니다. 그래도 동적이 아닌 부분은 분석 가능합니다.

base에는 없지만 profunctors에는 있는 흥미로운 클래스들도 몇 가지 있습니다. 예를 들어 Cochoice의 Arrow 상응물이 있다면 대략 이런 모습일 겁니다:

class (Arrow k) => ArrowCochoice k where

unright :: k (Either d a) (Either d b) -> k a b

unleft :: k (Either a d) (Either b d) -> k a b

구현에 따라 다르긴 하지만, 이를 사용해 재귀 루프나 while 루프를 구현할 수 있습니다. 이렇게 하면 ArrowApply를 사용해야 하는 흔한 필요성 하나를 피해 가면서도 루프 내용에 대한 분석은 보존할 수 있습니다.

profunctors에는 더 좋은 것들이 많으니 한 번 둘러보길 권합니다(고마워요, Ed). Traversing은 Traversable 컨테이너의 각 원소에 profunctor를 적용할 수 있게 하고, Mapping은 Functor에 대해 같은 일을 합니다.

아무튼, do-notation 바인드에서 임의의 함수를 쓰며 당연시하던 대부분의 행동은, 대체로 똑같은 일을 해내는 Arrow 타입클래스들의 조합으로 분해할 수 있음을 볼 수 있습니다. 여기서는 “최소 권한의 원칙(Principle of Least Power)”을 적용하는 게 좋은 기준입니다. 일반적으로는, 프로그램을 무리 없이 인코딩할 수 있는 가장 낮은 권능의 추상을 쓰는 편이 분석 가능성 측면에서 가장 강력한 잠재력을 보장합니다.

Functor–Applicative–Monad 효과 시스템에서 Category/Arrow 위계로 전환함으로써, 우리가 만드는 프로그램을 깊게 들여다보는 능력을 유지하면서 훨씬 더 복잡하고 표현력 있는 프로그램을 표현할 수 있음을 확인했습니다.

표현력을 더 얻기 위해 어떤 타입클래스들을 더 모을 수 있는지, 그리고 사용자 정의 인스턴스를 구현해 프로그램을 분석하고 심지어 도식화(다이어그램)하는 방법까지 살펴봤습니다.

마지막으로 Arrow 표기법을 훑어보며, 이런 류의 프로그램을 쓸 때 문법 부담을 얼마나 줄여 주는지도 확인했습니다.

그럼, 이제 Monads를 버리고 전부 Arrows로만 작성해야 할까요? 솔직히 말해, 저는 Arrow가 더 나은 토대라고 믿습니다. 지금의 Haskell 생태계가 Monads에 올인하긴 했지만, 만약 당신이 새로운 함수형 언어의 효과 시스템을 설계하고 있다면, Arrows를 한 번 써 보지 않겠습니까?

배운 게 있었다면 좋겠습니다 🤞! 만약 그렇다면 제 Patreon에 합류해 제 프로젝트를 따라오거나, 제 책도 확인해 보세요: Haskell 및 다른 함수형 언어에서 optics를 사용하는 원리를 가르치며, 초보자에서 시작해 온갖 종류의 optics를 다루는 마법사 단계까지 이끕니다! 여기에서 구입하실 수 있어요. 한 권 한 권의 판매가 이런 블로그 글을 더 쓰게 만들고, 교육용 함수형 프로그래밍 콘텐츠를 계속 만들 수 있게 도와줍니다. 감사합니다!